Cinemage

Cinemage (2005 - 2007)

slide projection of still photo images with live improvised music

Cinemage refers "images for cinema"and"homage for cinema." On this project, I show still photo images by old-fashioned slide projections. At times, with music which is improvised by solo or duo guitarist(s), or without music, silent. Cinemage can be shown as a performance, or an installation in gallery space.

The visual images are snapshots taken from my daily life. I apply similar methods developed from my work as a composer, particularly the ongoing project Cassette Memories, in which I play field-recordings which I keep as a sound diary. By documenting fragments of my personal life, something is revealed in their accumulation. The meaning of the original events are stripped of their significance, exposing the architecture and essence of memory.

Although most photographers slice out a single moment in time to render an image as absolute, my visual images consist of a moment within a movement. The sensibility is essentially filmic. The photos are more like moving images than stills and the style is similar to Chris Marker's La Jetée. Projected on a screen, the images have the eerie familiarity of an out-of-focus memory and evoke a feeling of déjà vu.

For this project, Loren Conners, Alan Licht, Noël Akchoté, Jean-François Pauvros, and Oren Ambarchi play guitar as solo or duo along with my visuals. The music is equally important as the visual images, and not just accompaniment. These musicians have been examining the relationship between visuals and sound in other projects, and bring a deep understanding of its possibilities to Cinemage.

Works

2007 After the Rain, color, 25 minutes

2007 Lost City, black & white, partially color, 35 minutes

2005 Something Which Wasn’t Said, black & white, 35 minutes

Performances

2009 Silent version, Uplink, Tokyo, Japan

With Noël Akchoté at La Casa Encendida Cultural Centre, Madrid, Spain

With Loren Connors at Lisa Cooley Fine Art, New York, USA

With Noël Akchoté in International Film Festival Rotterdam, The Netherlands

2008 With Noël Akchoté and Jean-François Pauvros at Foundation Cartier, Paris, France

With Jean-François Pauvros in Cimatics, Brussels, Belgium

With Noël Akchoté in AURORA, Norwich, UK

With Loren Connors in Media City at Detroit Film Center, Detroit, USA

2007 With Noël Akchoté and Jean-François Pauvros in Gent Film Festival at Vooruit, Gent, Belgium

With Loren Connors and Alan Licht at Anthology Film Archives, New York, USA

With Noël Akchoté in Wiener Festwochen, Vienna, Austria

With Oren Ambarchi and Alan Licht in Netmage, Bologna, Italy

2005 With Loren Connors and Alan Licht at Tonic, New York, USA

With Loren Connors and Alan Licht in Roulette Mixology Festival, New York, USA

Publication

2015 Aki Onda Lost City with Loren Connors and Alan Licht, Audio MER, Belgium

Review

Aki Onda Lost City with Loren Connors and Alan Licht

Dusted, USA, 2015

Text by Bill Meyer

In Chis Marker's La Jetée, still images accompany a spoken soundtrack, highlighting the way that people perceive moments in isolation even though they are part of an endless flow of time. The effect of this technique was not lost on Aki Onda, whose work with photographs and cassette tapes of field recording made on his journeys around the world considers the meaning of frozen pieces of pasts by sharing them with strangers in distantly removed places and times.

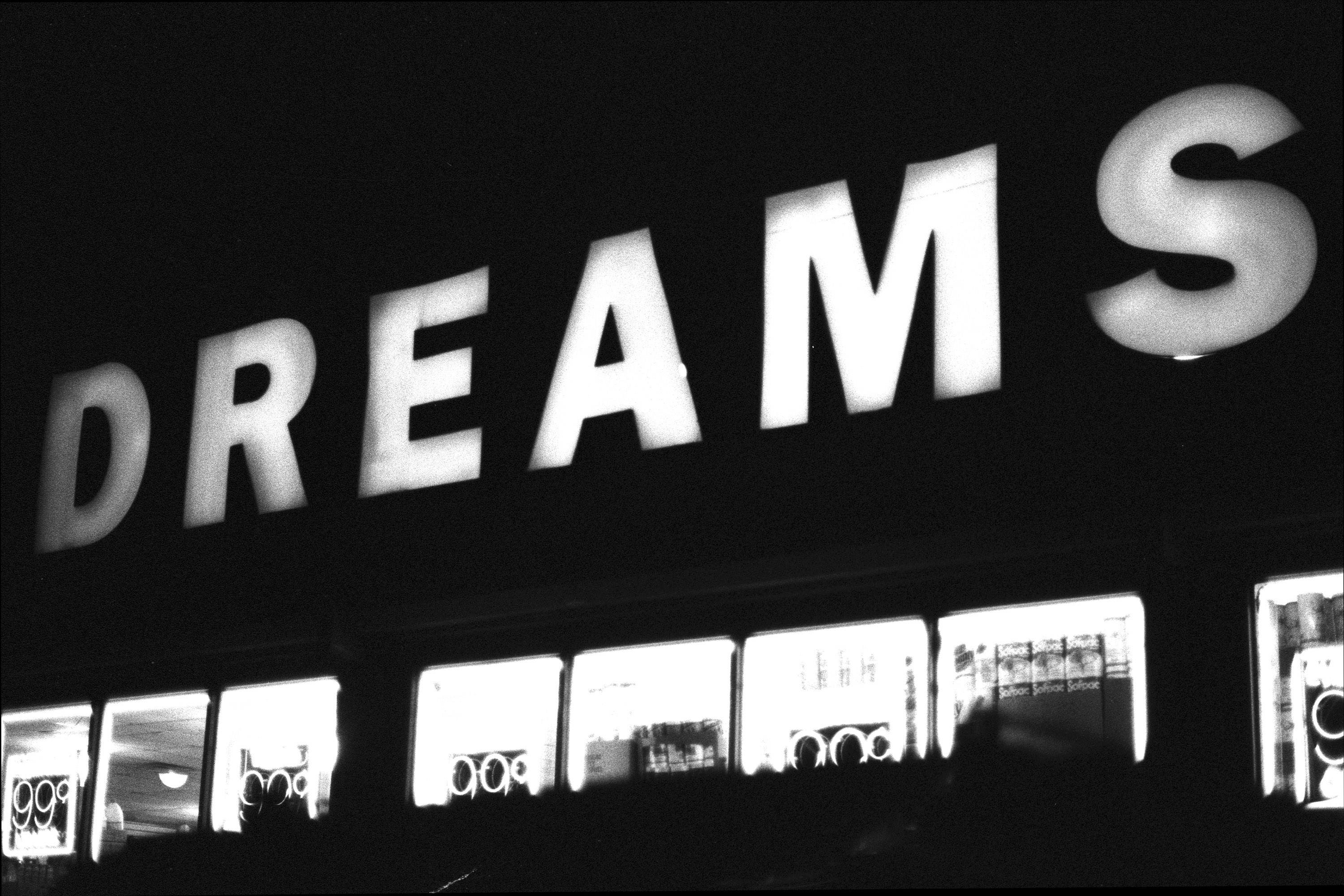

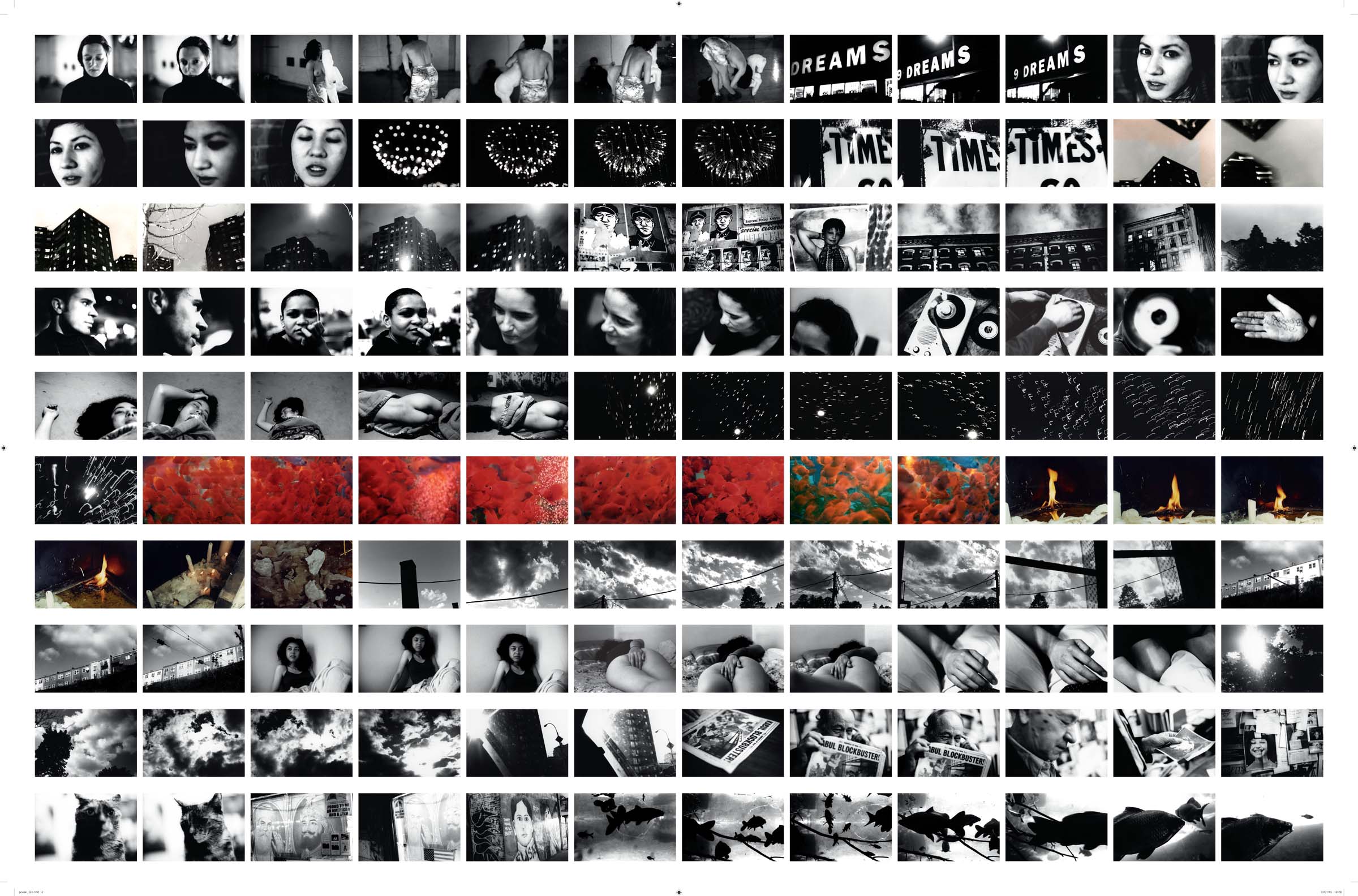

Onda moved to New York not long before the towers came down on 9/11/01 and this process became a way to manage both the collective trauma he witnessed around him and the fulminating fear and jingoism that followed it. The result is Lost City, a series of images that he showed by screen projection with accompaniment by guitarists Loren Connors and Alan Licht. The effect of filtering the grain of black and white film through the projection process corresponds to the sounds they selected and they way they are registered on this LP, which constitutes a physical documentation of the project. The LP's packaging is elaborate, with the record, a big foldout poster of Onda's pictures, and a pamphlet all encased in a heavy plastic sleeve; it's a hefty thing, game to defy the cold facts of impermanence.

Onda chose well when he elected Loren Connors to soundtrack Lost City. Connors has spent a quarter century incorporating loss and memory into his art. He has composed odes to long-dead icons and paved-over New York neighborhoods, and on a more personal level his playing is an ongoing document of his quarter-century long task of living with Parkinson's disease. The recordings, one a duet with the indefatigable Licht from 2007 and the other a solo from 2005, include coughs and shuffling that betray the situation of the microphone nearer to the audience than the guitar amps. What you get is a magnification of distant sound, grainy and flicking, much like the projections of Onda's photos must have appeared. Reverberation, room sound, and silence all bleed together with the stark notes, feedback groans, and suspended chords. On the duo side, the music is violent, full of jagged curves and explosions. The presence of such events within the murky entirety of the music corresponds to the unavoidability of trauma in life.

Liner notes

Transformation and Ekphrasis – Aki Onda’s Lost City

for Aki Onda with Loren Connors & Alan Licht, Lost City, audioMER 013 LP, Belgium, 2015

Text by Niels Van Tomme

“Transformation” has the character of a verb. Just like “imagination,” for example. Its product is change, not the state of things, for transformation signifies alteration. It is a process, which is most certainly directed against the human need for stability and constancy; on the other hand, transformation is a characteristic distinguishing the living from the non-living. The metamorphosis of things is disagreeable, however, partly because it brings deformation: transformation is only possible through the disintegration of an original shape or form dissipating in another, and partly because it leads to things apparently getting out of our control: hardly have we got to know something and it is already different and we have to start all over again.

- Miroslav Petříček

When Jacques Derrida arrived in New York City on September 26, 2001, two weeks after the events that would forever change “the course of world history,” to use the late French philosopher’s own words, he encountered a deeply traumatized city. Arriving during a period when most people would avoid traveling to New York, either out of fear for more catastrophes, or because of the advanced state of toxicity the city was in, Derrida stood by his American friends and colleagues, unconditionally supporting them in their prevalent sentiments of grievance and helplessness. The philosopher was profoundly struck by the events that preceded his visit, exemplified by his writing to a friend in a letter, stating that “the World Trade Center [was] a place dear to my heart, […] where I had hoped to take you, to enjoy, with you, from the 130th floor, the most beautiful view of New York.” At the same time, however, Derrida turned increasingly ambivalent about the sudden upsurge of patriotism and xenophobia he witnessed upon his arrival to the city. He also noted the far-reaching levels of indoctrination taking place through mass media channels and the way in which he had to use his words with considerable caution even in personal communications among friends.

Throughout those destabilizing and often confusing first weeks after the events, Derrida insisted on keeping a nuanced outlook, advocating that “giving up on complexity would […] be an unacceptable obscenity.” In retrospect, the philosopher’s insistence on rationality and analysis instead of disbelief and anger provided a refuge to deal with the sudden, violent changes in society and the feelings of loss and uncertainty associated with it. However, as much as Derrida’s much-needed, cautionary way of thinking and speaking might have provided a ground to reflect on a precarious situation of instability, it remained hard to imagine the multifaceted processes of transformation the city would be going through in the months to come—ranging from far-reaching and all-enveloping changes within the city fabric, as wells as the complex shifts in interpersonal relations.

During those confounding first twelve months, visual artist, field recordist, and sound performer Aki Onda, who had settled in New York in 2000 after spending considerable time here throughout the 1990ies, responded to the events by taking pictures, which he would later compile into a slide projector piece presented as Lost City. Seeking to create a record, a visual trace of that bewildering initial period, his response was decisively introspective. Looking at the images that, taken together, form the visual aspect of Lost City, they foreground intimacy and closeness in response to a markedly influential world event. Onda, in this specifically framed portrayal of New York City, thus emphasizes his immediate surroundings, attempting to highlight a “certain intimacy with everyday objects,” to use the words of cultural critic Svetlana Boym. Devoid of any direct references to the major event that sparked his impulse to start documenting things in the first place, Onda decisively switched his focus from the macro to the micro-level, thereby accentuating how politics, and the unfolding of world events, has foremost repercussions for the personal and intimate sphere.

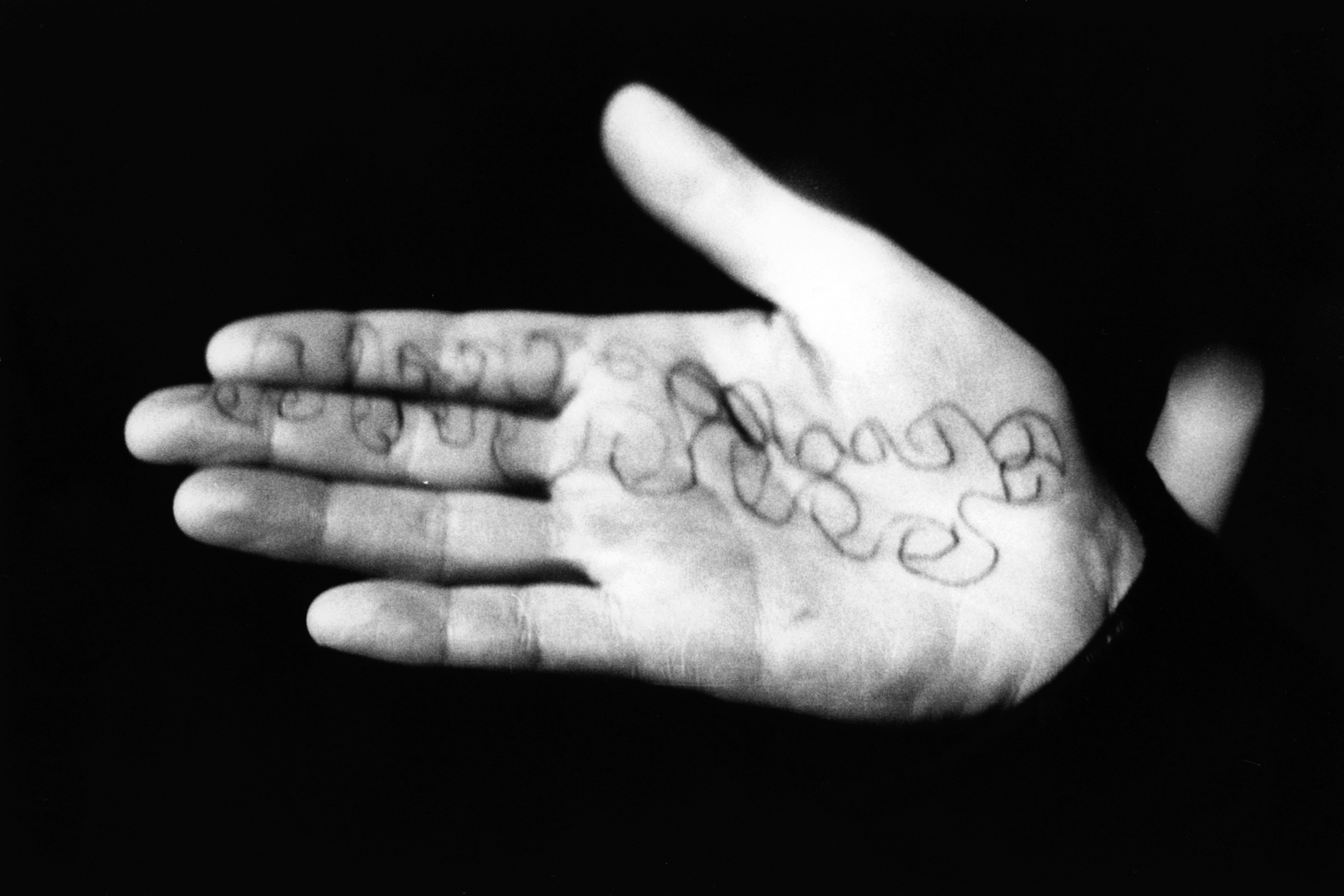

As photographs, these images considerably bypass photography’s traditional mode of understanding representation. With their undeniable focus on surfaces, light sources, movements, and gestures, they do not so much represent the ‘visual essence’ of the things they portray, as they emphasize photography’s ability to reveal flowing and contextual processes. Rather than providing an accurate account of events, these images appear to almost abandon the representational realm, offering an abstracted and decentered approach instead. Mostly shot in grainy black and white, except for a short sequence in bright red hues and color, they evoke oneiric imagery, stressing a certain lack, something that has disappeared and therefore cannot be captured again. As such, these images become empty surfaces on which to project original information that has inevitably been lost. Rather than creating a definitive, collective memory of the events, these images mimic the creative ability to remember such traumatizing incidents and their aftermath. They provide fuzzy imagery for something that is uncomfortably positioned at the cusp of oblivion, inexorably disappearing from view.

Taken together, however, the images form a composition, quite in the literal sense of the word. Conceptualized as a visual score to Lost City, they form the nucleus around which an improvised musical performance is constructed. To achieve this, Onda has worked together with two of his close collaborators, the experimental guitarists and composers Loren Connors and Alan Licht, with whom he has been performing the piece in a number of different contexts since 2002. Whereas traditionally a visual score still adheres to a notation on paper, with visual symbols replacing conventional music notation, Onda’s score is a composition over time due to the basic structure of a slide projection, a succession of images lasting roughly thirty to forty-five minutes. As such, its compositional aspect should be mainly thought of in a temporal-visual realm, to which the improvising musicians are invited to respond. Onda has repeatedly referred to the score as “cinemage,” defined as a way of making moving images using still photo imagery and old-fashioned slide projectors. Ending up with slow cinematic sequences at a frame rate of seven to fifteen seconds, with a dark gap between each image, this process is opposed to the usual, fluid twenty-four frames per second that underscores filmic movement and imagination.

There is of course something inherently nostalgic about the use of slide projection technology. An undeniable part of our collective cultural memory, it hints at times past when the format was frequently used in a number of educational, corporate, and familial contexts. Simultaneously, its sounds, its immediately recognizable clicks and jolts, add another, aural level of familiarity to the ritual. Rather than accentuating such nostalgic and somewhat commonplace features of the device, however, Onda’s singular, decisively uncharacteristic and unsentimental use of this disappearing technology accentuates processes of transformation instead of nostalgic contemplation.

Within this transformative context, it seems useful to evoke the Greek concept of ekphrasis. This term references a rhetorical device in which one medium of art attempts to relate to another, resulting in an altered aesthetic experience. According to literary scholar Christopher Rovee, ekphrasis is a “self-reflexive exercise in representation, […] a mimesis of a mimesis,” in which a visual object is vividly described with words, be it orally or in literature. Even though it is conventionally understood in such terms, music scholars such as Siglind Bruhn have more recently argued that musical representations of visual art may be defined as ekphrasis as well. Here, the relationship between Aki Onda’s visuals and their musical interpretation becomes apparent, framed as a continuously mutating, transmedial, and metaphorical process. Ekphrasis, then, instead of its conventional reading, should be seen as an active aesthetic device that foremost reflects processes of transformation, an idea which is further emphasized by writer Mai Al-Nakib’s statement that “it exposes a mutability of forms since, by definition, it is the expression of one form of representation in terms of another.”

In the hands of Aki Onda, the slide projector, rather than being an old-fashioned nostalgic device, becomes a machine of transformation enabling a process of musical ekphrasis. This remarkable constellation, leaves Loren Connors and Alan Licht completely free, responding, each in their own idiosyncratic ways to the rhythm and shapes of the images that are slowly floating by, enabling a multifaceted interplay of audiovisual mutability. Viewed as such, this exceptional collaboration enables yet another process of transformation in which the sharing of ideas, as well as the continuous exchange between composed imagery and improvised sound, reflect a foremost communal experience. Exemplifying a complex process that enables one to come to terms with the rupture and instability caused by traumatic events, it importantly reflects the reality Aki Onda originally started working with while capturing his immediate environment. The piece, then, ultimately echoes the multifaceted processes of transformation the city and its manifold communities went through in the months following the events. As it so aptly responds to the shifts in the urban landscape and the experiences associated with these modalities of change, it ultimately restores a sense of community by staging a process of transformation that is not merely produced, but can also be shared communally as it reaches its audience.

The National September 11 Memorial and Museum is preparing to open its doors in New York City in the spring of 2014, and the ‘official’ history of the event and its aftermath will soon be staged within its walls, no doubt exhibiting all the challenges related to the straightforward construction of such national narratives within a museal structure. While this context will stage 9/11 within an official setting of remembrance, Aki Onda’s Lost Cityremains as an ongoing reaction to the event from a “minoritarian position,” to use Deleuze and Guattari’s suggestive term, infinitely enriching the ways we continue to understand it, and interact with its memory. Far removed from the slick architectural smoothness, political performances, and corporate visibility that surrounds the construction of official narratives of commemoration, Onda offers a decisively fractured and experimental approach that destabilizes the very notion of remembrance. Rather than repeatedly staging a definitive account, his performance piece, through the multifaceted processes of transformation outlined above, constitutes a kind of ‘counter-memory,’ a fluid, uncertain, and transformative interpretation of the events. As such, Aki Onda’s Lost City could be coupled to the subtle and analytical, yet deeply emotional initial responses expressed by Jacques Derrida, joining the French philosopher in thinking through memory and narrative in more private, and less straightforward ways than the ones that continue to be dictated to us through rigorous, and ultimately limiting processes of monumentalization.

New York City, May 2014