Interview with Gozo Yoshimasu

By Aki Onda

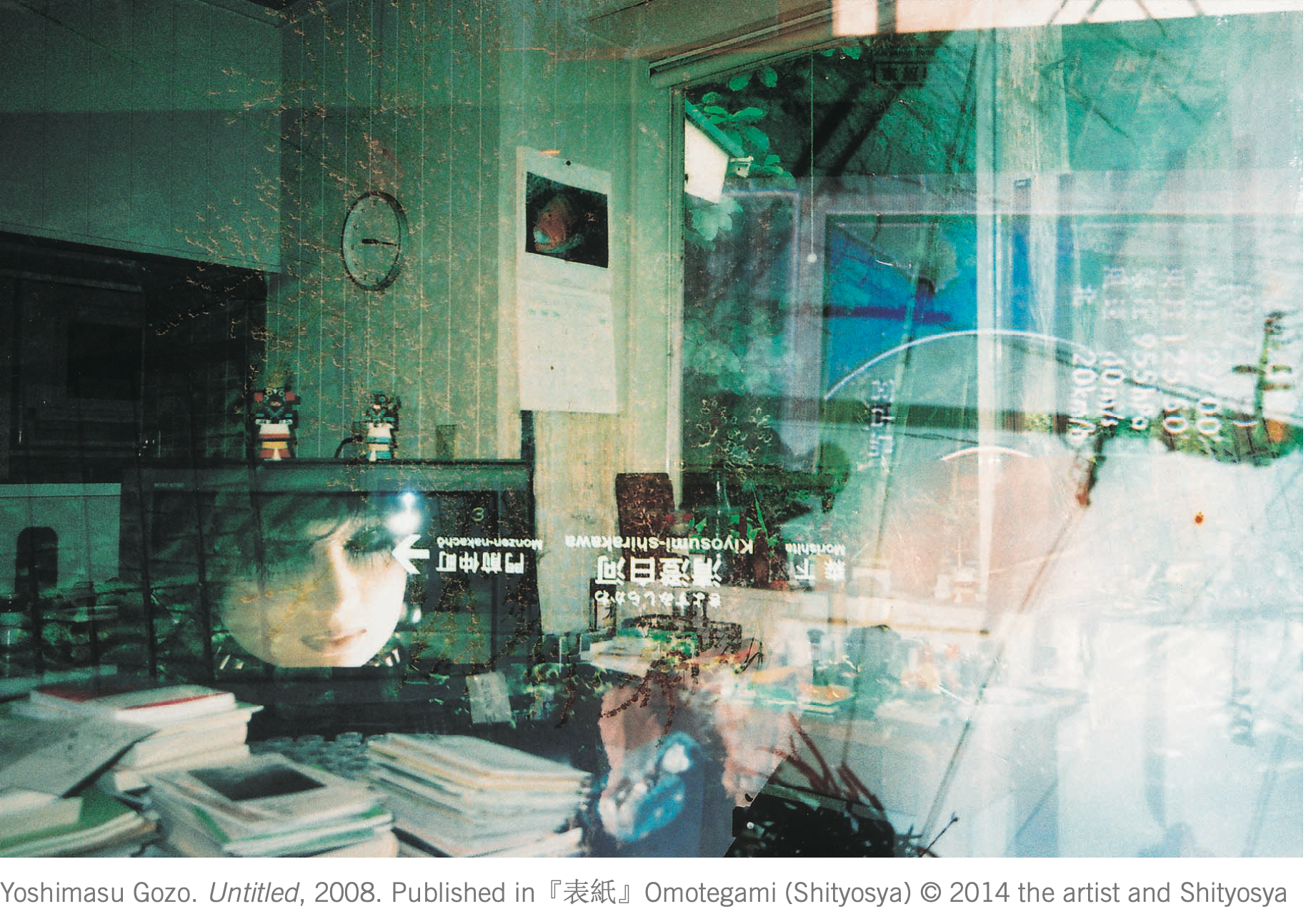

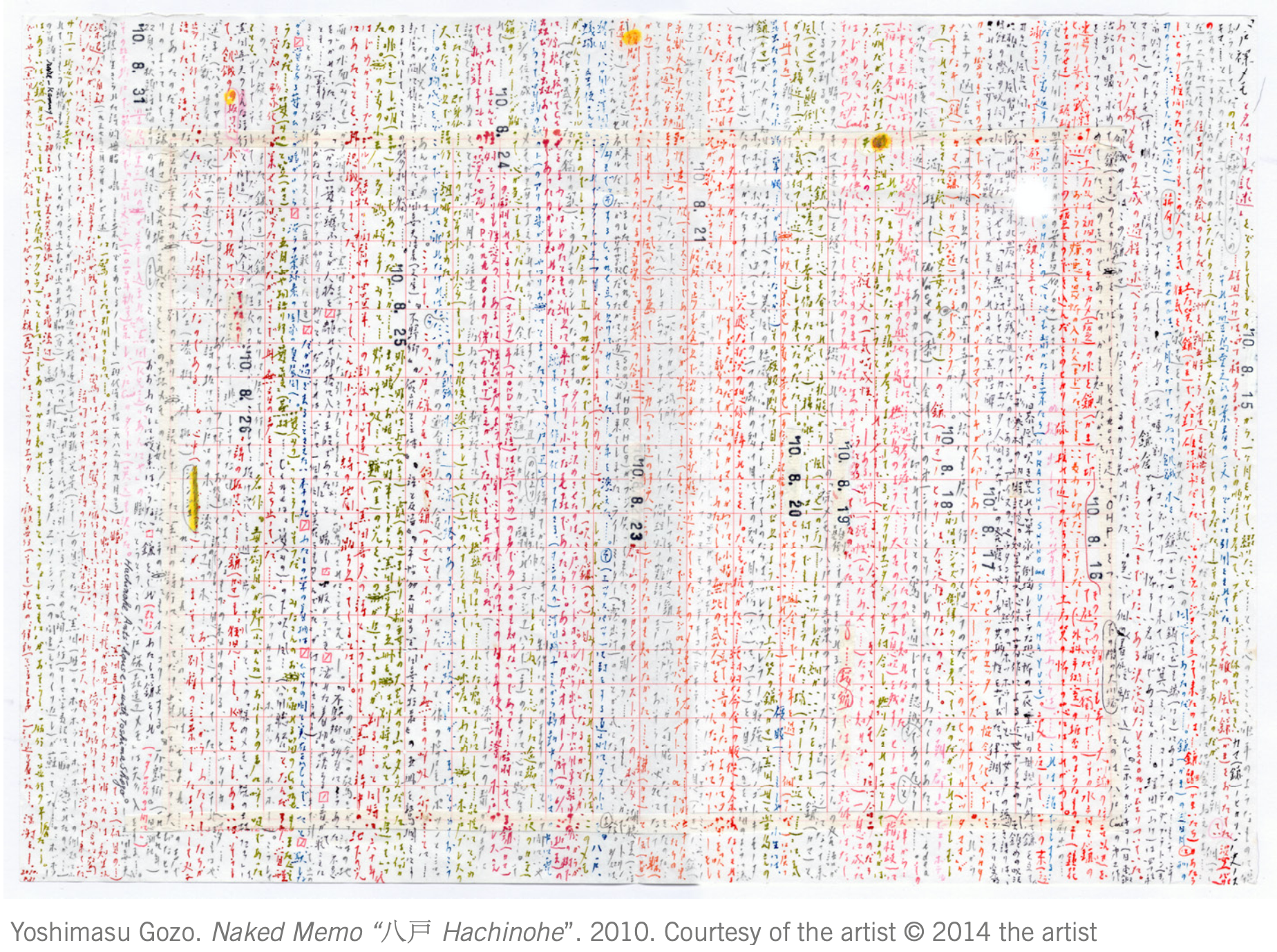

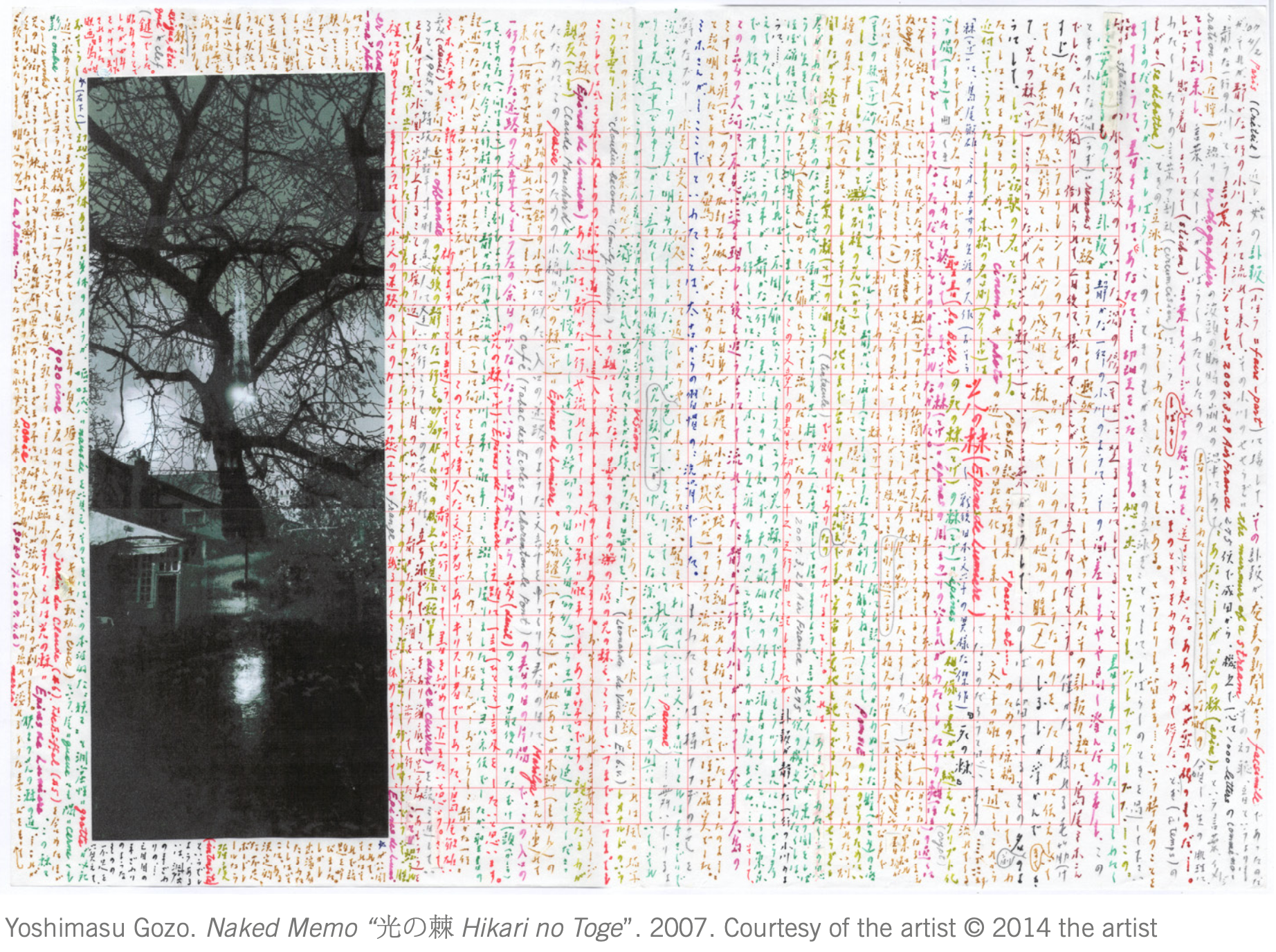

Yoshimasu Gozo’s creative endeavors have spanned half a century since the publication of his first book of poetry, Shuppatsu (Departure), in 1964. During this time he has cultivated a singular art form without parallel in postwar Japanese poetry. Some of his work is so unorthodox that it defies the print medium and can be delivered only as performance. Yet, although he has at times been regarded as a maverick, his unending quest to elucidate the essence of poetry places him firmly within a time-honored tradition. Perhaps because he came of age creatively during the 1960s and 1970s, when the Japanese cultural landscape was in its golden age of multimedia experimentation, he has never hesitated to branch out into other media: since the late 1960s he has collaborated with visual artists and free jazz musicians; in the late 1980s he began creating art objects featuring words engraved in copper plates; and recently he has produced photographs as well as a series of video works entitled gozoCiné. Today, at the age of seventy-four, his appetite for creative exploration shows no sign of abating. This interview was conducted at the Pink Pony café in Lower Manhattan on October 1, 2012, the day after Yoshimasu and the guitarist and turntablist Otomo Yoshihide had wrapped up a performance tour of five North American cities.

ONDA: Yoshimasu-san, first of all I’d like to ask you about the cultural landscape of Japan in the 1960s and 1970s and about where you fit into it. You published your debut collection of poems, Shuppatsu (Departure), in 1964, right around the time you graduated from Keio University. What was going on in Japan in those days?

YOSHIMASU: The conflict over the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty was raging, and that cast a long shadow over my student years. Of course, the sixties were a time of Americanization in Japan, and there was wave after wave of cultural influence: in literature there were the Beats, and in music there were folk singers like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, who were followed a bit later by the Beatles. When I think back on those days, when I was in college, the person who played the single greatest role in introducing the work of the Beats to Japanese audiences was Suwa Yu. He was a poet, a translator, and an all-around great guy, and he organized frequent readings of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Kaddish. In Tokyo he launched a magazine called Doin’,— which dealt with music, photography, and poetry—and others, including Shiraishi Kazuko, Okunari Tatsu, Kusamori Shinichi, Okada Takahiko, and Sawatari Hajime, got involved. Suwa Yu was championing this cutting-edge poetry from the United States, and his circle was at the forefront of the poetry avant-garde in Japan.

Along with the poetry came jazz by Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane. The early sixties were really a cultural explosion on all fronts. Then, of course, the visual arts were hugely important, and spearheading the avant-garde was Takiguchi Shuzo. He was a leading champion of Surrealism in Japan and a unique character of the sort you rarely saw there. Takiguchi was originally a protégé of Nishiwaki Junzaburo, but he was truly a free spirit and, at the same time, a diligent, sensitive, and profound thinker. The cadre surrounding him included Isozaki Arata, Arakawa Shusaku, Takemitsu Toru, Tono Yoshiaki, and O’oka Makoto. There was also Hijikata Tatsumi, the Butoh dancer and choreographer. There was Terayama Shuji. All these people formed a sort of galaxy around Takiguchi Shuzo, and they were the movers and shakers who shaped Japanese culture during that era, at least from a visual arts point of view.

The next generation was that of Akasegawa Genpei, Nakanishi Natsuyuki, and Takamatsu Jiro, who made up the Hi Red Center group. Then there were the photographers Taka- nashi Yutaka, Nakahira Takuma, Moriyama Daido, and Taki Koji, who established the magazine Provoke in 1970 and made a major mark on photography. All these people were loosely clustered in one great galaxy, and artistic movements in postwar Japan took place in that context. Ikebana artist Nakagawa Yukio and Butoh dancer Ohno Kazuo were right in the hub of this galaxy as well. The action unfolded in venues like Minami Gallery, Tokyo Gallery, and the Tsubaki Kindai Gallery in Shinjuku. Art and literature flourished and intersected in this environment.

ONDA: I see. And did the poet Suwa Yu, who introduced the Beat poets to Japan, have a place in this galaxy as well?

YOSHIMASU: No, I don’t see him as part of that galaxy. He was off on his own, a maverick. His colleagues in the field of British and American literature looked at him askance, and, in fact, he had plenty of enemies. He walked a thorny path in life and came to an early end, but I absolutely think he should not be overlooked. He translated Howl andKaddish and the poems of Gregory Corso as well, I believe. He lived in Nerima Ward in Tokyo, and the literary crowd used to refer to him sarcastically as the “beatnik of Nerima,” but I think what he did was really important. He led the way in promoting the culture of poetry readings and “little magazines”—noncommercial literary magazines that publish work by emerging writers— a movement to which Shiraishi Kazuko belonged as well. This was real subterranean stuff, even deeper than the so-called underground.

ONDA: So, what kind of relationship did you have with Suwa Yu?

YOSHIMASU: Suwa-san read my Shuppatsusoon after I published it in 1964 and asked me to write something for the second issue of the literary magazine Subterraneans. I still treasure my copy of that magazine. Around that time an extremely intimate yet totally open, genre-bending mentality prevailed.

ONDA: And that mentality coincided with the other things going on at the time, whether it was the Beats or the anti-Security Treaty movement?

YOSHIMASU: I think it was right around that time that Kenneth Rexroth came to Japan. He was the man they called the “father of the Beats”—a big, rough-edged guy, a member of an earlier generation of poets. After Rexroth, younger poets like Ginsberg and Gary Snyder came to Nanzen-ji Temple in Kyoto. Kyoto was always a hot spot.

ONDA: So you got the chance to meet some of the American Beats?

YOSHIMASU: That’s right. Also, Robert Rauschenberg came to Japan in 1964 and did a performance called Twenty Questions to Bob Rauschenberg at the Sogetsu Art Center, which led to the creation of his famous work Gold Standard. Around that time, some brilliant guys from the French literature department at the University of Tokyo, like Tono Yoshiaki and Iijima Koichi, had formed a group that studied Surrealism, and their breed of art criticism was beginning to be a dominant cultural force in Tokyo. All of them were stars in the Takiguchi Shuzo galaxy.

ONDA: Hmm, it’s interesting that Takiguchi Shuzo himself originally specialized in French culture, but that later, American culture began making inroads into that galaxy of his.

YOSHIMASU: One of the big influences there was Marcel Duchamp, who fled France for New York, in a kind of self-imposed exile. The same is true of Max Ernst. We can’t forget the fact that America’s avant-garde had connections with France. Arakawa Shusaku made New York his base of operations as well. As French intellectuals migrated to New York, France ceased to be the global cultural epicenter. Even Claude Lévi-Strauss followed this same path. And the Japanese cultural landscape of the sixties, formed around Takiguchi and the other followers of Surrealism, echoed this trend. Of course, this is mostly information I gleaned from magazines and hearsay, though I’m talking as if I experienced it firsthand. I try to avoid talking like that.

ONDA: So would you say that Japanese intellectuals were learning from the French, and as the French drifted over to New York, the Japanese followed that trend, discovering contemporary American culture and starting to import it into Japan?

YOSHIMASU: That about sums it up.

ONDA: What kind of place was the Sogetsu Art Center?

YOSHIMASU: In ikebana flower arranging, there are conservative schools like Ikenobo and Koryu, and I believe the Sogetsu school was an offshoot of Ikenobo. Teshigahara Sofu, an incomparable ikebana genius and the father of the film director Teshigahara Hiroshi, established the school. Out of the old soil of this tradition-bound world sprouted the most innovative of movements, and it revolved around the Sogetsu Art Center. The Teshigaharas were wealthy and had this fantastic venue, and it grew into a kind of cultural ground zero. Meanwhile, in those days the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper sponsored a big annual exhibition called the Yomiuri Independent. Kaido Hideo, the chief editor of the Yomiuri’s arts section, was the driving force behind the Independent, and a lot of talented artists made their debuts there. The exhibition had links with Sogetsu, and Takiguchi’s circle had ties with both as well.

ONDA: It sounds like it was all connected, that there were no barriers in those days between the visual arts, literature, dance, and other fields.

YOSHIMASU: The lack of barriers back then was staggering, when you look at the way things are now. The arts were a “liberated area,” to use a phrase in vogue around 1968. In terms of poetry, the early sixties Kyoku movement was revolutionary. It was spearheaded by Amazawa Taijiro, Suzuki Shiroyasu, and their associates. At the same time other movements were gradually emerging in political activism, popular music, popular entertainment districts, art criticism, Ankoku Butoh dance, the jazz scene, and the avant-garde theater of Terayama Shuji and Kara Juro. Terayama and Kara had ties with Takiguchi Shuzo through the dancer Hijikata. The thing about Takiguchi was, he was quiet and mild-mannered, but he always showed up in person when something was going on. No matter how small or insignificant an event, he was always there in a corner watching it. That’s not something you can say about any old egghead critic.

Takiguchi’s golden protégé was Takemitsu Toru. Most composers would name another composer as their primary mentor, but Takemitsu calls Takiguchi his greatest teacher. That gives you some idea of how wide-ranging Takiguchi’s influence was. Others who cite him as a mentor are the artist Arakawa Shusaku and the architect Isozaki Arata. He was at the center of all this artistic activity, straddling all kinds of disciplines. He had a playful side, which he showed by doing things like making handmade passports and distributing them to young friends of his, and he was a defiant nonconformist as well.

ONDA: That must be why he was able to forge bonds with people from such different fields. What kind of work did Takiguchi himself do?

YOSHIMASU: His best-known piece of writing is Kindai Geijutsu (Modern Art), but he was also known as a Surrealist and was recognized for his presence alone, his originality and primordial energy. Yet although his associates viewed him as a legendary art critic, in the academic world and among those outside his circle, he was undoubtedly seen as a dubious character. Late in life, he became obsessed with producing works using the technique of decalcomania.

ONDA: What kinds of connections were there between Takiguchi’s circle and the Sogetsu Art Center?

YOSHIMASU: I wasn’t terribly close to that circle and so I couldn’t tell you exactly, but there was a journal called SAC, which was a kind of all-around arts magazine. They paid the writers very well, since the Sogetsu organization had plenty of money. Various critics under Takiguchi’s influence, like O’oka Makoto, Tono Yoshiaki, and Nakahara Yusuke, wrote for the magazine. On the film side of things, there was an odd magazine called Eiga Geijutsu (Cinema Art), which revolved around the late Ogawa Toru. Some of its writers were Yoshimoto Takaaki, Mishima Yukio, O’oka Makoto, and Iijima Koichi. All of these magazines, SAC and Eiga Geijutsu, as well as Kikan Film (Film Quarterly) and Bijutsu Techo (Art Notebook), were very open-ended and broad-minded. As for literature, the journal Eureka hadn’t come out yet; I suppose the big one was Gendaishi Techo (Modern Poetry Notebook). Magazines in those days weren’t as rigid as they are these days. They were open to all kinds of things. The same is true of the arts sections of newspapers. There were lots of talented writers around.

ONDA: So it wasn’t just the magazines, it was also the quality of the writers.

YOSHIMASU: Part of it was that journalism in Japan was still a youthful field. However, Takiguchi never wrote for the newspapers. As far as I know, he only wrote one piece—about Surrealism. He kept his distance and played the role of a sort of paterfamilias to the avant- garde artists. Around this time there was a big to-do over Akasegawa Genpei’s trial for print- ing fake thousand-yen bills, and Takiguchi acted as his special counsel. In this crucial case, in which Akasegawa was being prosecuted for what they were calling an antisocial act, Takiguchi stepped forward and offered his support. Whenever there was something of importance going on, Takiguchi was sure to be there.

ONDA: What kind of engagement was there with American culture during this period?

YOSHIMASU: The name on everyone’s lips, the mythic figure, was Marcel Duchamp, and John Cage was seen as part of the same sphere. Then a few years later, in the latter half of the sixties, there was the poetry/jazz movement. Takiguchi was not involved in that. Rather, when it comes to jazz, it was the people at the literary magazine VOU—Shimizu Toshihiko, Okunari Tatsu, Shiraishi Kazuko. Then, I think it was in 1971 that Jonas Mekas’s film Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania came to Japan. I can still clearly remember the impact of that. The artist Nobuyoshi Araki appeared around that time, and I think the filmmaker Iimura Takahiko was on the scene earlier than that. These people really shook things up, I think.

ONDA:In those days, I think most people in Japan, aside from the kind of prominent people you mentioned, had limited access to information about what was going on in America. Not many people saw the films of Mekas, viewed the paintings and performances of Rauschenberg, heard the poems of Ginsberg, and kept abreast of the New York under- ground. Do you think people were aware of the scene in New York?

YOSHIMASU: I myself was not.

ONDA: So you didn’t have the overall picture, but you had glimpses—through Mekas and Ginsberg, for example—is that correct?

YOSHIMASU: That’s about right. Much, much later, in the late eighties, I attended a party held by Mekas in New York, and Ginsberg was there, and I finally started to connect the dots. I guess I was slow to pick up on things.

ONDA: The reason I ask is that it seems that Takiguchi Shuzo and the Japanese intelligentsia brought an enormous amount of information about Surrealism and French culture into Japan, but that when it came to the New York scene, the overall level of awareness in Japan was pretty low.

YOSHIMASU: You’ve got a point there, Onda-san, but on the other hand, if you were interviewing someone else you might get an entirely different picture of what was going on. For example, if you asked Kosugi Takehisa, Shinohara Ushio, or Matsumoto Toshio. . . . In 1964 Tono Yoshiaki published a book called Gendai Bijutsu (Contemporary Art). He had traveled to the U.S. and gone around seeing the contemporary art scene close up, in New York especially, and turned what he saw into this book. That was really a momentous event, one that greatly elevated what you call the level of awareness of the American scene. For me, in particular, it certainly did.

ONDA: That’s interesting. All this information trickled into Japan from here and there, bit by bit.

YOSHIMASU: One very influential aspect of American culture was jazz. At the Pit Inn in Shinjuku, Yamashita Yosuke performed alongside Elvin Jones, who had been arrested for drugs and couldn’t go back to the U.S. A Butoh dance troupe danced at some of the perfor- mances, and people started doing things that combined poetry and jazz.

ONDA: And wasn’t it around that time that you started reading your poetry aloud with live jazz accompaniment? What exactly led up to that?

YOSHIMASU: It was at the Pit Inn in Shinjuku, with Suwa Yu running the show. The person who originally proposed the idea was Soejima Teruto, the most radical jazz critic at the time. Around 1968 he suggested combining poetry with free jazz, and the events got started in the New Jazz Hall on the second floor of the Pit Inn, which was really just a glorified broom closet. There were some performers who are now legendary—Abe Kaoru, Takayanagi Masayuki, Oki Itaru—but the audience generally numbered about two or three, with five or six people performing.

The well-known actor Tonoyama Taiji often attended, and one time when we were doing a radio program together, he said, “You know, there are five or six of you guys performing, but the audience consists of me and about one other person.” They were doing a kind of very explosive experimental jazz. Then I was invited by Soejima to work with a jazz combo, and I dove right into the jazz performance and recited a poem called “Kodai Tenmondai” (Ancient Astronomical Observatory).

ONDA: What style did you adopt when reciting the poetry?

YOSHIMASU: Well, the music is frenetic, right? It’s so noisy you can’t make out what they’re playing. So my voice builds up to a scream. When I was working with musicians, I felt I had crossed over from the audience’s side to the performers’ side, and I could do anything I felt like. It was an amazing feeling.

ONDA: You must have gone outside the bounds of merely reciting poetry.

YOSHIMASU: That’s right. I felt like I, myself, was an instrument. I remember some of the jazz people raising their eyebrows and saying, “Man, what kind of vocalist is this?”

ONDA: Did you perform anywhere besides the Pit Inn?

Yoshimasu: A long time afterward we performed at a little theater dedicated to puppet plays, called Pulcinella, on the third floor of a small building across the street from the Tokyu Department Store’s flagship store in Shibuya. That was through Suwa-san as well. We did a lot of performances combining jazz and poetry readings there. Around 1972 we also did an avant-garde show of jazz and poetry at the Ikebukuro branch of Parco.

ONDA: How did you start collaborating with the guitarist Takayanagi Masayuki?

YOSHIMASU: Soejima Teruto introduced me to the bassist Midorikawa Keiki, and we had a great partnership for quite a long time. Midorikawa was associated with two more experienced musicians, one of whom was Takayanagi Masayuki, the guitarist. The other was the percussionist Togashi Masahiko. I participated in a session, along with Midorikawa and Takayanagi. There were also sessions where I worked with Midorikawa and Togashi, but it was with Takayanagi that I got into some of the farthest-out stuff. When performing with him, to be honest, I was at a loss sometimes. The volume was so incredi- bly loud, you know? I couldn’t even hear what was going on. It went beyond what a guy like Haino Keiji was doing, Takayanagi was intentionally going overboard. [Laughs.]

ONDA: Despite the decibel level, he wanted to add a poetry reading on top of it? [Laughs.]

YOSHIMASU: When the sound was well balanced, you could hear the recitation as one more sound source, but a lot of times it was just lost in the chaos.

ONDA: Do you have any recordings made during that period? I know a CD of Takayanagi Masayuki and Midorikawa Keiki’s Shibito (Dead Person) was released, but is there any- thing else?

YOSHIMASU: Just like you, I have tons of old tapes lying around. My apartment is knee-deep in hundreds of cassettes.

ONDA: All right, I’ll have to come over and poke around.

YOSHIMASU: I’ve got so many old tapes, you won’t believe it. [Laughs.]

ONDA: Were there lots of poets collaborating with jazz musicians, and did the trend spread throughout the poetry world? Or was it just you and your associates?

YOSHIMASU: My personal impression is that it did not, by any means, spread throughout the poetry world. The world of literature is by nature extremely conservative, and that of poetry is even more so. They scorn and deride any attempt at showmanship, like mixing in singing or anything playful. There’s no way that collaborating with musicians would ever be a mainstream thing. In fact, a lot of people still have a reflexive dislike of poetry’s being read, period.

ONDA: I see. Was there anyone besides you who was involved in it, then?

YOSHIMASU: Well, the person who pioneered it was Shiraishi Kazuko. In the early days Shiraishi worked with Tomioka Taeko. Shiraishi-san had had a really rough time of it, having been born in Canada as well as being a woman, and so she was a rabble-rouser from the core.

ONDA: A few years ago I saw Shiraishi Kazuko performing opposite Oki Itaru at the Bowery Poetry Room. She radiated an incredibly powerful aura. Just her sheer eccentricity. . . . She obviously doesn’t give much credence to authority.

YOSHIMASU: She certainly doesn’t. Tomioka Taeko went over to the literary world, but by contrast, Shiraishi Kazuko has insisted on sticking to the same path for all these years. Most poets, if left to their own devices, will end up moving in purely literary circles or being swallowed up by academia.

ONDA: Yes, there’s not a lot of money in poetry. [Laughs.]

YOSHIMASU: There sure isn’t. [Laughs.] These people are facing financial issues. After all, you can’t survive on stubbornness alone.

ONDA: In which years were you performing with jazz musicians?

YOSHIMASU: Hmm, when was it? I guess for about fifteen years starting in 1968. However, as a matter of fact, I don’t like reciting poetry. Essentially, I prefer writing it. What I’ve kept throughout, as an underlying philosophy, is the quest to reclaim the poetry that I believe lies at the root of all performing arts. It’s not just a mere poetry reading. To the audience I may have looked enthusiastic but, in fact, I always felt a bit weak in the knees when I was doing it.

ONDA: Personally, you would rather have focused on writing poetry and kept the performances as a sort of sideline.

YOSHIMASU: That’s right. I’ve been consistently fascinated with the materiality of language, but when it comes to getting onstage or performing with language, I’ve always had my doubts and I still do. It might sound like a contradiction, but. . .

ONDA: I suppose when one is pursuing the direction you’ve been pursuing—deconstructing the language that poetry is built from—then performance is one way of expressing those ideas, although writing itself is always at the base of things.

YOSHIMASU: “Deconstructing” makes it sound like a deliberate act of the intellect, but I think the motivation for performing comes from somewhere deeper, from the fundamental creative instinct. I think it’s clear to see, looking through the poetry books that I’ve published. In the mid-seventies the publisher Kawade Shobo approached me about releasing a collection of my complete works. I was still young, and releasing my complete works was something I’d never even dreamed of. I wasn’t ready to be placed in that position, you know? And so I frantically went about writing a three-part work called Neppu (Devil’s Wind), which was a thousand lines long, for the magazine Umi (Sea). I incorporated marks, like dots, lines, and brackets, into the text, so that it would be impossible to read aloud. But I ended up reciting it anyway. For me, reading aloud is a terrifying thing, and so I memorize the poem beforehand. But when you memorize it and recite it, it becomes just like the lyrics to a pop song or something. You have to demolish it somehow. I know this instinctively, and the way I do this is to write the demolition into the poem itself.

ONDA: To me, the way those punctuation marks are used looks like a form of breathing.

YOSHIMASU: That’s right. It’s also a form of breathing. Sitting down to write a thousand lines is tough, right? And so you skip some lines, ha-ha-ha. But you have to make it look like the spaces are pauses to take breaths.

ONDA: And so the blank lines are part of the text. There are the words, and then they’re interspersed by. . .

YOSHIMASU: Silences.

ONDA: I see. You wove silences into the text.

YOSHIMASU: Usually, they count only the actual lines of text, but here, there were punctuation marks and spaces and things, and I got paid for those lines as well. [Laughs.]

ONDA: A technique you struck on when you were under duress.

YOSHIMASU: Around that time I was making repeated trips to Mt. Osore [Mt. Fear, in northern Japan, said to be the “gateway to the other world”—translator’s note]. It was a trek; the Tohoku Expressway was still only half completed then. The first time I went was when an American poet named Thomas Fitzsimmons and his wife were staying with me, and I thought it’d be a kick to show them Mt. Osore. But I had a shock there.

ONDA: What gave you a shock?

YOSHIMASU: It really is an intermediate zone between worlds.

ONDA:What did you do there? Did you see a shaman, or a medium?

Yoshimasu: Yes, we did. The mediums are pariahs; they’re not allowed on the premises of the main temple at Mt. Osore. They lay down straw mats off to the side of the temple and sit on them. Not one of them is like another. And they’re all blind, you know. So we sat down next to them, and I was thrilled with the spectacle. What could be more dramatic? They’re supposedly possessed, with the dead speaking through them, but it’s all a bit fishy. [Laughs.]

ONDA: What they’re saying couldn’t strictly be called “words,” right?

YOSHIMASU: That’s right. It’s not words so much as tones and melodies. You feel a really incredible vibration from them. In Kabuki, there are scenes in which female characters express powerful emotions in a chanted lyrical monologue called kudoki, and it sounds something like that. It’s just nonsense, like, “I see the tree of heaven, it bears the fruit of the sacred name of the Buddha, ohhh. . . .” Some of them are really good at it, others are not so good. [Laughs.] The not-so-good ones are merely prosaic. The great ones are superstars. I brought along a tape recorder, sat down next to an old woman who struck my fancy, and recorded her, though I couldn’t comprehend the Tohoku dialect. Sony had released a portable tape recorder in 1974 or 1975, and to be able to walk around with a tape recorder felt revolutionary. I brought the tape I had recorded to a local hot spring inn and got one of the maids there to interpret it for me. That was really something. “My name is blah blah blah, I went off to war but I came back empty-handed, and then. . . .” She spoke in a thick Tohoku accent and used the word “hettei,” which I couldn’t understand. When I asked what “hettei” meant, she told me, “Heitai, heitai”––a soldier.

ONDA: So you see this medium, and she’s channeling some spirit from the “other world.” What were you hoping to get out of this experience?

YOSHIMASU: When the spirit was coming on, she rattled this instrument like a kind of net made of seashells. It was a rudimentary thing, but she was able to produce a real aura of drama with this makeshift instrument and the sutra she was chanting. It really shook me up. After that, when I watched something like Hijikata Tatsumi’s Butoh dance performance in Ikebukuro, I’d get bored with it. It paled in comparison to the medium’s performance, I realized. She was the real deal.

ONDA: You mean Butoh is just too polished and civilized.

YOSHIMASU: Once what someone is doing gets called art, it immediately becomes merely acting, a mere transmission of information. I realized that this kind of thing was going nowhere fast. And so I started traveling to Mt. Osore regularly and making tape recordings. Then I’d hole up at a hot spring inn there in Aomori Prefecture and go over them with a fine-tooth comb. I remember a moment when I suddenly understood what she was saying in her thick Tohoku accent: “I’m cursed with bad luck.” It was a revelation. I spent a long time going through the tapes like that.

ONDA: Did you make transcripts of them?

YOSHIMASU: I did. I still have them all. I transcribed them for dear life. I guess writing is in my blood. [Laughs.] I published them in a magazine called Bungakkai (Literary World).

ONDA: There’s a phrase “geijutsu no ibuki,” literally, the “breath of art,” but what this “breath” means to me is vibration. Something that is not yet concrete, but still seeking form. I guess you felt this vibration directly from the mediums.

YOSHIMASU: It was fantastic. It almost had the resonance of a circus scene in a Fellini film.

ONDA: What sort of influence did it have on the form your poetry recitation performances took?

YOSHIMASU:The northern Siberian shamans do everything themselves, just like the mediums. They strum instruments, suspend lamps from their necks; they create all these kind of oscillating circuits. They’re all abuzz like human insects. I think I’m trying to get to a similar place––before I start reading a text, I always think about what noises I’m going to make, how I’m going to sit, and so on, taking the whole process as one of connecting with something. When I traveled to Mt. Osore and sat with the mediums, I was trying to absorb the atmosphere they created with the instruments and noises they made so that I could do a similar thing myself. It took me thirty or forty years to realize this. I’ve been wounded by comments that compared me to a shaman and so forth, but that was really just “tears of ignorance” on my part.

ONDA: The work that you’ve done over half a century, which in narrow terms you could call poetry, and in broad terms you could call a revolt against the Japanese cultural establishment––all these attempts to head off in entirely new directions in writing or performances and so forth––have you been subject to prejudice because of these?

YOSHIMASU: Maybe so. I certainly have a deep-rooted instinct toward provocation, or rebellion. And, as I’ve realized in the course of this conversation we’re having, I have a deep respect for “the materiality of language” and innate “ignorance.” Those lie at the root of my poetry. Or perhaps it’s anger.

ONDA: From what I’ve heard from you today, it seems like the cultural climate of Japan in the sixties and seventies was one in which anger like that was accepted. Like culturally, there was a fundamental openness to anything, including the kind of new things you learned from Takiguchi. Or to put it another way, the culture at the time was deeply anti- authoritarian. My impression is that you were lucky to spend your younger days, when you were learning and developing creatively, in a climate of antiestablishment rebellion.

YOSHIMASU: You’re right. For fifty years my hand has never stopped writing poetry. I’ve published more than twenty books of poetry. Looking back on it now, there must have been a reason for it. No matter how tough things got, I never stopped writing. The performances may have been a way of replenishing my energy to write more poems. But now, even today, I write poems so that they can’t be read aloud. For example, “Rasenka” (Spiral Song) is impossible to read aloud. One thing’s for sure: something I start out writing with the intention of reading it aloud will never be any good. [Laughs.]

ONDA: Excuse me for changing the subject, but in the 1970s you went to America to take part in the Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa, didn’t you? Were you teaching there?

YOSHIMASU: No, no. They just invite writers from all over the world and provide them with an ideal climate for writing. For seven months, from autumn through the following spring, you’re given no obligations whatsoever.

ONDA: Did your direct encounters with American culture have an impact on your work?

YOSHIMASU: What came over me then—and I think this is something that’s still happening to me today—was not an urge to try to learn English and immerse myself in American culture, but rather something that was eating away at the language I use instinctively in everyday situations. I wondered, why am I making no effort to learn English? It was because another language, Japanese, which I use for creative expression, was getting in the way. And so I had a bit of a nervous breakdown, and this withering away of language became my jumping-off place. That was quite an important turn of events.

ONDA: You didn’t attempt to speak English or to enrich your Japanese, but rather took steps toward making yourself wordless and seeing where that led you creatively.

YOSHIMASU: Looking back on it now, that was true silence. True quiet, something on the scale of the entire universe. You could also call it poetry.

ONDA: While dwelling in the world of poetry, which is one of words, you were attempting to use something other than words in order to transcend words.

YOSHIMASU: That’s right. It was constant torment, that’s for sure. The torment comes and goes in waves. You ask yourself questions, like, “Is it just that I have no talent?” and then answer them yourself. After that I went to Michigan and had the same experience, and then I went to São Paulo and had the same experience again. And then I realized there were cracks forming in the very foundations of my command of language and it was withering of its own accord. What made it even more painful was that I was writing through all of this.

ONDA: And from there, you went in a new creative direction.

YOSHIMASU: Right. And I finally arrived at an awareness of the act of “causing language to wither” and came up with the phrase for it. It’s an exaggeration to say it took half a century, but it did take forty years or so.

ONDA: Which book of poetry did you write around that time?

YOSHIMASU: What I wrote after returning to Japan were extremely chaotic works, “Okoku” (Kingdom) and “Waga akuma barai” (My Exorcism). I wrote these despite the state I was in.

ONDA: You kind of felt your way along when you were writing them.

YOSHIMASU: Well, I always do that. I’m not led by my intellect. It’s something more primal. I’m driven by the impulse to wrest something from the words I encounter.

ONDA: Where do you think this impulse comes from?

YOSHIMASU: I wonder where. It doesn’t come from knowledge or experience. I really think I’m similar to one of those blind old mediums babbling mystical nonsense about the Buddha.

ONDA: I don’t think there’s anything so mysterious about the mediums’ behavior, though. The mediums have always been oppressed, downtrodden. From this they’ve acquired some special capabilities. They have certain techniques for transmitting the world’s vibrations.

YOSHIMASU: Yes, you said it right there. Transmitting the world’s vibrations—vibrations that reach into and touch every area of a person’s life. The mediums are all gone now; their tradition has died out. But the amazing thing for me is that, if it hadn’t been for those encounters, my life would really have been a dull one.

ONDA: Finally, I’d like to ask you about Takemitsu Toru. Takemitsu had a really open mind, just like Takiguchi Shuzo. He was a contemporary composer, but in addition to composing film soundtracks and so forth, he was a prolific writer. And he served as director of the Music Today festival, which was held from 1973 to 1992. He brought all sorts of composers from overseas and constantly breathed life into Japanese culture. He also introduced a lot of Japanese composers to audiences outside Japan. He was a cultural ambassador and a cultural icon. I feel he has something in common with you, as you both refuse to be pigeon- holed, but instead dismantle categories, destroy them, clear space away so that new forms of creative expression can blossom. Have you had any interactions with Takemitsu?

YOSHIMASU: Yes, we had a dialogue that’s transcribed in the Chikuma Bunko publication Takemitsu Toru taidan sen: Shigoto no yume, yume no shigoto (Selected Dialogues of Takemitsu Toru: The Dream of Working, the Work of Dreaming). Among Takiguchi’s protégés, he had the greatest mind. And he was an odd guy, with no higher education.

ONDA: That’s right, he never went to high school, much less to university.

YOSHIMASU: Right, and he came of age right after the war ended. At one time he was working part-time at Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo (Tokyo Telecommunications Engineering Corporation), the predecessor of Sony. At that time “Sony” was just the company’s logo or nickname, or something like that. At first it was just a glorified version of one of these small local factories. Then along came tape recording and magnetic wire recording, and suddenly all kinds of sounds were being recorded. This means that Takemitsu was there right at the dawn of tape recording in Japan. He was a nuts- and-bolts guy, but then, when he went under the tutelage of a Surrealist intellectual like Takiguchi, his talent blossomed splendidly.

ONDA: I heard an interesting story from Otomo Yoshihide. He said that when Takemitsu heard the first film soundtrack that he [Otomo] had composed, for The Blue Kite, Takemitsu called him up and said he wanted to meet. He must have felt a sense of kinship with me, Otomo supposed. Then when they actually met, what Takemitsu said was, “You know, I was using turntables as an instrument first, man.” [Laughs.]

YOSHIMASU: So Takemitsu had that side to him, huh? [Laughs.]

ONDA: He did feel a sense of kinship with Otomo, but out of that, perhaps, came a sense of rivalry. From what you told me just now about tape recorders, rather than having a formal musical education, Takemitsu got into music from the standpoint of breaking it down into component parts, but he ended up as a respected and acclaimed contemporary composer. However, he also composed a lot of film soundtracks and even pop songs, and he never lost his ability to relate to ordinary people.

YOSHIMASU: Part of it has to do with timing, I suppose. If Takemitsu had been born just five years later, he might not have experienced the postwar Allied Occupation era, when Sony grew out of a small neighborhood factory, in the same way. It seems like destiny.

ONDA: Destiny defined by history, you could say.

YOSHIMASU: I sent him books of poetry on several occasions and got letters back from him. That was really a wonderful thing. Like Takiguchi, when Takemitsu had a direct personal connection with someone, he was very good at expressing this closeness and comradeship.

ONDA: You were in-your-face and antiauthoritarian, whereas Takemitsu was more mild mannered. However, you shared a similar mentality, you both brought a lot of people together, and you also both bent and obliterated boundaries between genres. He talked constantly about his lack of formal musical education not really because it gave him an inferiority complex, but more as a badge of rebellious authenticity. If you look through all of his writings, you find him making statements to this effect throughout.

YOSHIMASU: You’re right on target there. Speaking of Takemitsu, during performances I sometimes dangle this rock called “sanukite” from my mouth. Takemitsu struck this same material, sanukite, to make the sound of the wind blowing in scenes featuring the snow-woman ghost in Kobayashi Masaki’s 1956 film adaptation of Lafcadio Hearn’s Kwaidan. It’s a musique concrète technique, but it’s an example of how imaginative he was as a composer. That really drew me to him.

ONDA: Where do they mine sanukite?

YOSHIMASU: It was originally mined in the Sanuki region on the island of Shikoku. That’s where the name “sanukite” comes from. There’s an undersea land bridge from there to Nara and the Kawachi region on the other side of the Seto Inland Sea, in Honshu, and it’s found there, too.

ONDA: Where did you get your sanukite from?

YOSHIMASU: In the Sanuki region, they call it a “ding-ding rock” or something like that —because of the sound it makes—and sell it at souvenir shops. I got some and carried it around with me. When I was teaching at the university, when I was talking about Takemitsu Toru, I told the students about sanukite. Then at some point, I went from teaching about it in the classroom to doing it myself. The sound Takemitsu produced was processed in a musique concrète manner, and so it’s a little different from the natural sound of sanukite, and I wanted to hear what the original sounded like. Also, I just like beating on rocks and things, and so that’s another reason for it. If you want to beautify it, you can call it an extension of Takemitsu Toru or an homage to his work, but there’s both more and less to it.

ONDA: Right, there are more factors involved. In any case, when you channel somebody or something, you’re not just mimicking it, you’re also taking steps toward grasping its essence.

YOSHIMASU: We certainly talked about a lot of heavy stuff today. It was fun, but even more than that, it was heavy.

ONDA: Some of this stuff is kind of scary, isn’t it? [Laughs.] But artistic expression, creating something, is always connecting to something larger.

YOSHIMASU: After talking about all of these things, I get the sense that I’ve already fulfilled some small part of my lifelong dream. Thank you so much.

ONDA: Thank you.

translatd by colin smith

——————

This interview was originally published in Japanese and English on post: notes on modern and contemporary art around the globe, the digital platform of C-MAP, MoMA’s global research initiative, on February 4, 2014.

This interview was also published in Gozo Yoshimasu’s book “Alice Iris Red horse,” edited by Forrest Gander, and published by New Directions in 2016.